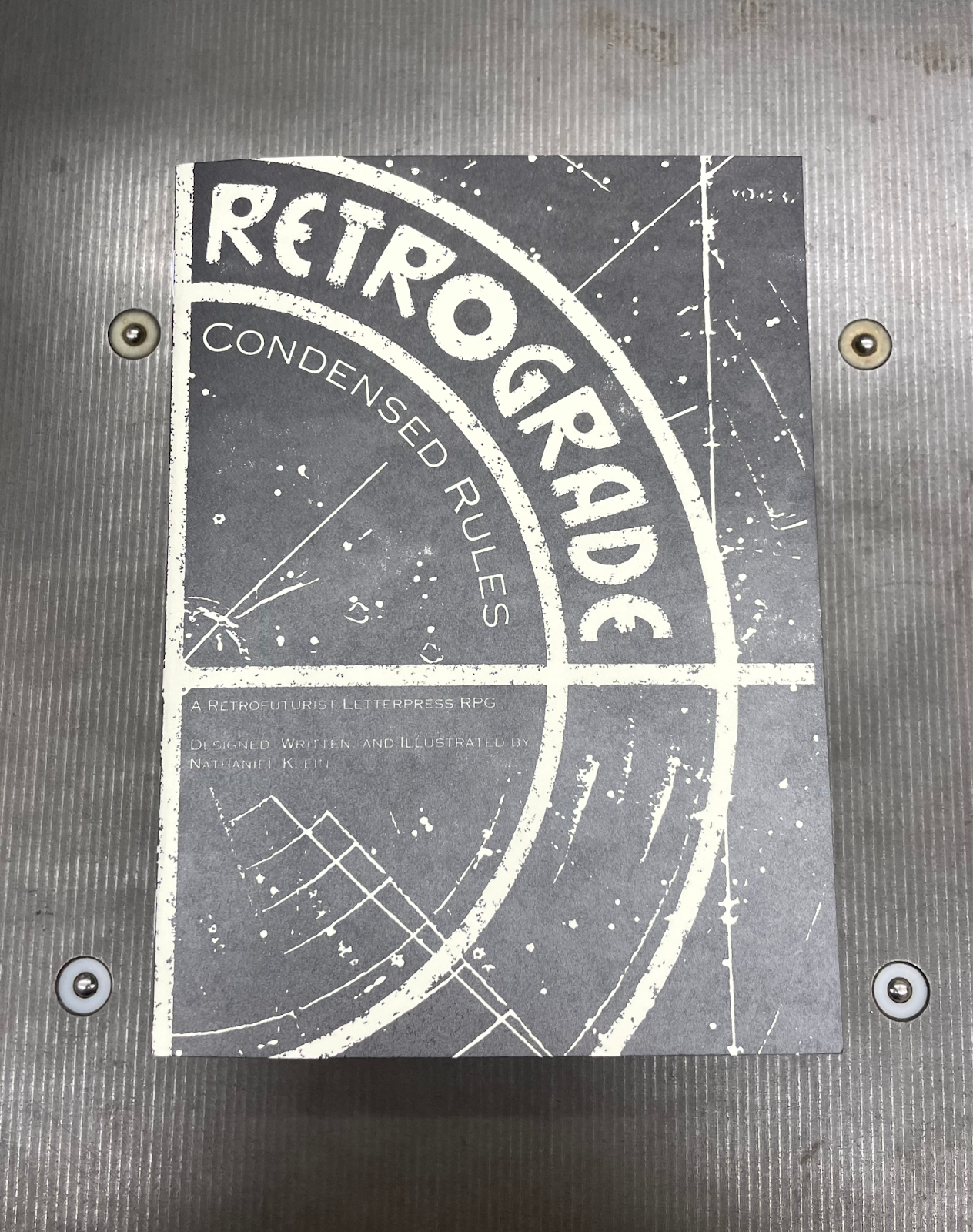

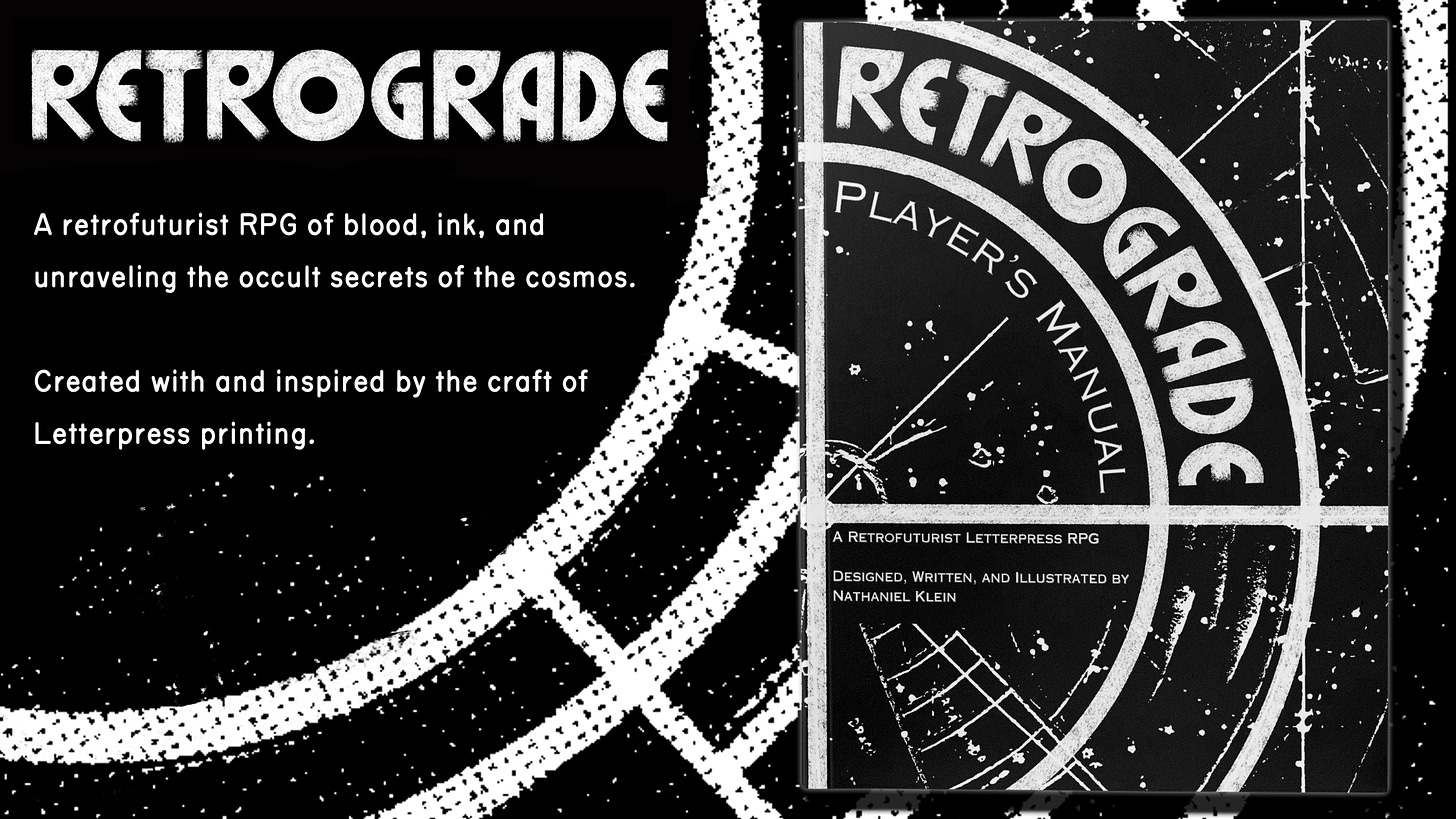

Printmaking is one of the primary artistic disciplines I pursue, and letterpress has positively captured my imagination. Letterpress runs throughout the process and product of Retrograde, my retrofuturist tabletop role-playing game inspired by letterpress printing and printed in hand-bound booklets with letterpress covers and linocut illustrations. While I’ve become profoundly inspired by letterpress, I’ve arrived at that inspiration relatively recently: I started pursuing printmaking about two years ago and actively started letterpress printing just last year. Despite the relatively small timescales, my passion for letterpress has built upon years of creative experimentation in a variety of forms, and it’s easy for me to see how those experiments have culminated in Retrograde’s development and physical creation.

My journey to letterpress began with an idea to physicalize my writing, printing a short story of mine in a booklet where the binding and typography were not merely a vessel for my story, but an expression of the narrative itself. Linocut seemed to me like the easiest place to start: I read Designing Your Life a few years back, and it had articulated a concept of “prototyping,” finding a low-commitment, low-barrier-of-entry way to start trying to do something that has captured your imagination. I bought a carving tool and a linoleum block for $20 and sat down to start carving the first page of my 5,000-word story.

I abandoned that particular version of the project after carving the first three words took me three hours. But nevertheless, that first carving unlocked something powerful in me: there was clearly an aesthetic power from the hand-carved feel of my first experiment, and there was a care and control in the process of carving that gave me a confidence I had not found in previous visual art experiments.

I had told myself for years that I could not draw; that skill would forever be impossible, and all of the possibilities that could unfurl from possessing such a skill were permanently locked to me. I don’t know exactly where that idea came from, but part of it stemmed from a hand tremor that I thought made fine detail and controlled strokes impossible, and somewhere in my youth I’d picked up a notion that this handicap made visual art in its entirety something I simply could not do. That belief was challenged in a college set design course: I had to draw as a requirement for my major, and my professors told me that, of course, I could learn how to draw. Anyone could.

While most of my time in undergrad was focused on directing plays and writing my first novel, I still wanted to explore the discovery I had made that I could learn to draw. By the time I graduated, I was able to crystallize that intention into a plan of action: if I wanted to learn how to draw, I could create my own experiments to teach myself how.

Experimentation was something I’d had good practice in from theatre. My hippie high school encouraged me to find ways to independently create my own work, and I put on several bizarre sci-fi plays throughout high school, including one in the DC Fringe Festival (which got panned in the Washington Post). In college, my professors trained me in Devised Theatre, a form that creates a theatrical script through collaborative improvisational experiments and encourages non-traditional pieces and rehearsal structures.

Some of those theatrical experiments blew up dramatically, or simply did not amount to a riveting, well-constructed story (as that Wa-Po article demonstrates). Few of those projects were exactly what I wanted them to be, but in each of those experiments I learned something that I applied to my next project. That chain of theatrical experiments made me more willing to make mistakes – trying something without being sure whether or not it would succeed was a key part of my creative process, and embracing the lessons inherent in mistakes would be key to improving my skills. I also got to see the results of continued experimentation on the same project and the power of revision: a devised theatre play to which I contributed text and performed in for a college class went on to be produced in the Edinburgh Fringe Festival two years later.

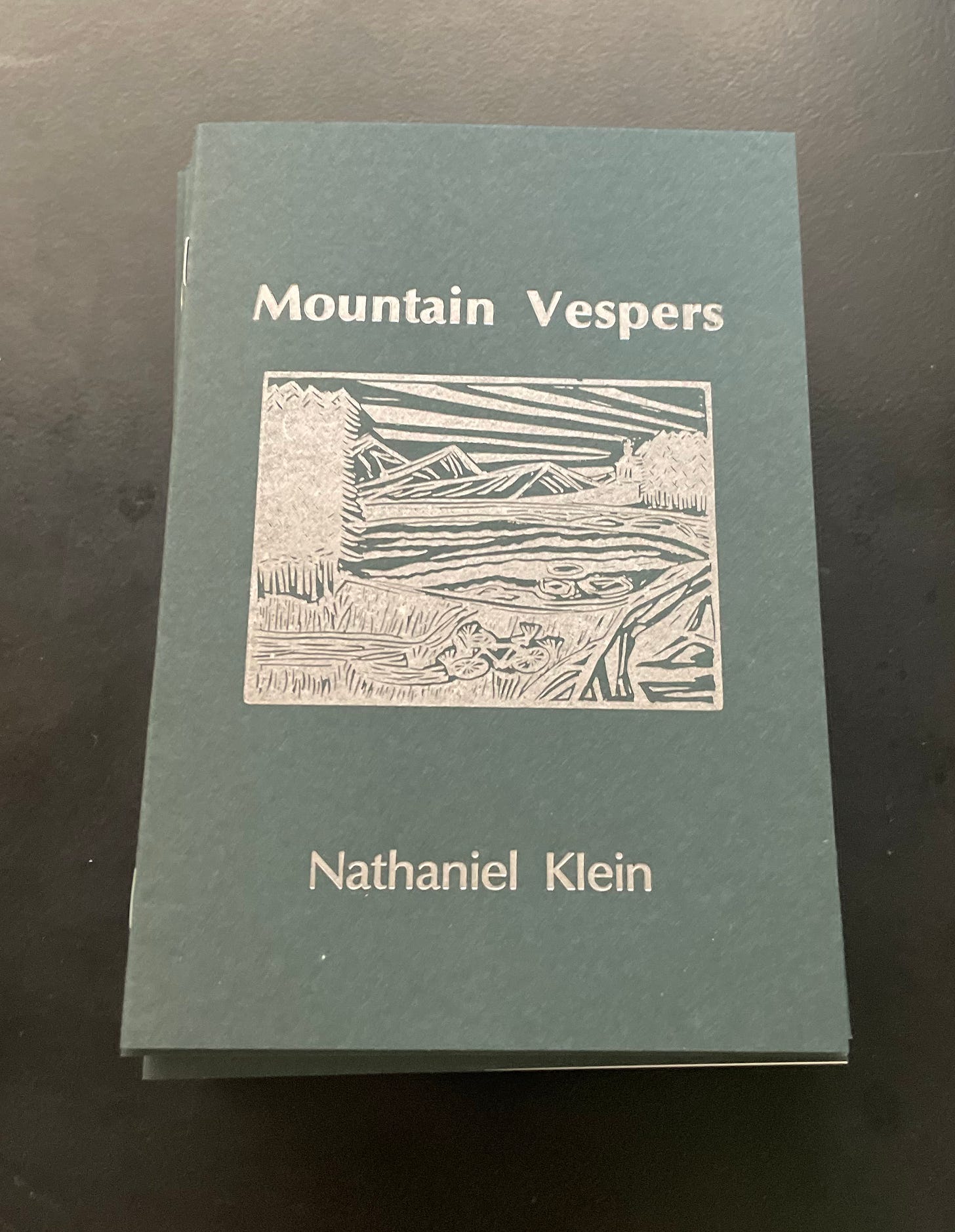

With this experience in experimentation, I knew that my skills and comfort in any medium of artistic work would grow over time, and any missteps would have valuable lessons – though my first attempt to render my writing physically with linocut was clearly not going to be feasible, my imagination was thoroughly captured, and I began drawing up further experiments. I bought myself some more lino blocks, carving tools, paper, and pencils. I watched some youtube videos to learn about carving techniques and started creating illustrations for a short story of mine, The Eye of Zosimos. Bookbinding could be another avenue for physicalizing my story: I ordered a small bookbinding kit on Etsy and started experimenting with coptic binding, and made a mesh sieve from a thrifted picture frame to hand-make recycled paper. I still wanted to create my story with a hand-crafted typography, something with more variation than a fixed typeface and, ideally, more physical than printing from a conventional home/office printer. It would be a labor-intensive task no matter what, but I had an old typewriter that I thought would do the job. I only made a few copies before two typewriters broke – the paper I had made was thick and uneven and did not feed well through a typewriter. Despite the project coming to a halt, the experiment had given me wonderful new knowledge and practice with skills I was eager to improve: I had physicalized my writing with papermaking, bookbinding, and linocut illustrations, and the act of laying out all of the elements together was a new skill in and of itself. Immediately, I wanted to find more experiments to further develop these new skills.

I started researching how people use analog printing methods to physicalize their writing, and I quickly arrived at letterpress. Letterpress would allow me to put together my writing, illustrations, and handcrafts with a distinct physical feel: the physical impressions in paper that letterpress printing can make would add a compelling physical dimension to my narrative work. Best of all, it was clearly feasible and accessible: my local community college had a letterpress course, and I could immediately begin prototyping letterpress experiments.

The world of letterpress was incredibly fascinating: composing type was satisfyingly tactile in much the same way as linocut carving added a more tactile dimension to my visual art experiments, and there was a magic in the versatility of what I could print on the presses. I was able to combine my linocuts with the letterpress shop’s type collection, resulting in my first major letterpress experiments. Letterpress was an accessible and effective way for me to physicalize my work and share it with others – a key component of my early letterpress experiments was learning techniques from my instructors and finding inspiration in the compositions of my peer printmakers.

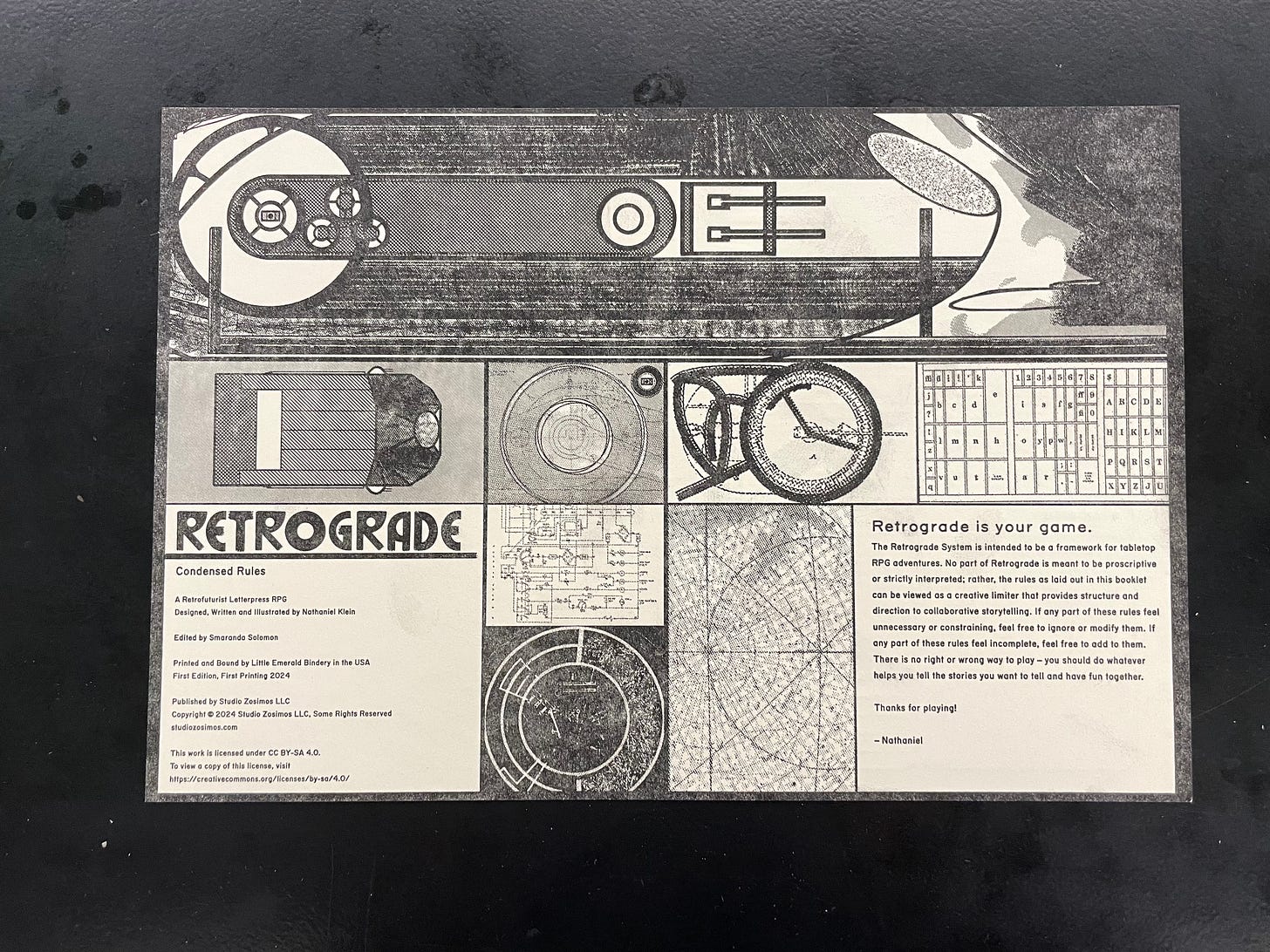

These letterpress experiments spontaneously led to yet another new passion: RPG design. I first played Dungeons & Dragons when I was 8 and properly got involved in the hobby in college. Playing through campaigns with my theatre friends gave me an appreciation for the character-driven, narrative-focused games possible with RPGs. After trying out a few different rules systems, I wanted to design a system that would encourage exactly the kind of gameplay I loved. Letterpress made the idea of creating my own RPG and putting it out into the world feel feasible, and I started designing my ruleset in earnest. Alongside my rules, I developed an analog sci-fi world for my game, built upon an esoteric, alchemical cosmology I’d been developing in my fiction. That world was powered by letterpress, with starships built to be massive printing presses that teleported across the stars, carrying newspapers to distant planets faster than digital information traveling at the speed of light could reach. That world quickly found a name: Retrograde. After some months of experimentation with systems design, writing, playtesting, and illustrating, I was ready to print the first edition of the Retrograde Condensed Rules booklet.

While I have only been working on Retrograde for about a year now, it’s clear to me that creating the game wouldn’t have been possible without years of experimentation across multiple artistic disciplines: my experiments with theatre, fiction, linocut, bookbinding, and letterpress are an essential part of Retrograde. Each of those experiments compounded upon each other, giving me new lessons, leaving me with new creations, and creating new questions that only further experimentation could answer, evolving into an alchemy of process and product, of troubleshooting and discovery, of effort and frustration, of obstacle and reward, of making mistakes and learning from them, of sharing my work with others and daring myself to face the new, open to mistakes and the lessons that come with them, endeavoring to walk an ever-branching path that, so long as you decide to keep walking it, will arrive at creation.

Indeed, there is something magical and transformative about these experiments. They are an essential part of the process of creating my work, but the content of my work is also implicitly imbued with the process of their creation. I’m immensely eager to share the story of those creations with you.

If you’d like to see where my next experiments lead, you can follow Retrograde on Kickstarter, check out my Instagram, subscribe to this blog, and share this post with your friends on social media. Supporting my work and sharing it with others helps me to find new experiments and improve my work, and I hope that we’ll be able to build a creative community together.

Thanks for reading!

–Nathaniel